Paediatric ACL Injuries: Are We Seeing An Increase?

2020 has certainly been an unusual year. It started with devastating fires followed by a global pandemic. After a period of lockdown, home schooling and cancelled sports, in much of Australia we have seen a gradual lifting of restrictions. I have noticed over the past few months as school sport has returned a higher number of adolescent patients presenting with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. This may just be coincidental and reflect referral patterns but it started me thinking that the shortened or in some cases even non-existent pre-season training may be a factor. I wanted therefore to dedicate this newsletter to the topic of anterior cruciate ligament injuries and in particular those in the paediatric population. There is a lot we can do to reduce the incidence of these injuries and I think educating schools, clubs and coaches is the key.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury has a level of concern in the paediatric population. Do children who rupture their ACL mature similarly to their non-injured peers. It is well recognised that adult patients with an ACL may develop symptoms and features of osteoarthritis within 10 years. There is very little evidence to guide decision-making in the management of paediatric ACL injury. ACL injury in childhood may significantly compromise the patient’s quality of life, increase their risk of further injury and limit their ability to return to sport. For these reasons prevention of ACL injury is important because of the serious long-term consequences.

In 2017 the International Olympic Committee hosted an international group of experts including physiotherapists and Orthopaedic surgeons who specialise in paediatric ACL injuries. Their aim was to develop a consensus statement on prevention, diagnosis and management of paediatric anterior cruciate ligament injuries to guide treating physcicians. This statement was published in the Orthop Journal of sports med in March 2018.

Anterior cruciate ligament injury is one of the most common knee injuries. The anterior cruciate ligament runs from the posterolateral femoral condyle to the anteromedial tibial plateau. It limits anterior translation of the tibia and also limits or checks rotation. Historically, tibial spine avulsion fractures were considered the paediatric equivalent of ACL tears. We are however, seeing an increase in presentations of mid-substance ACL injuries in children and adolescents. This may reflect and increased awareness and therefore increase diagnosis but it may also reflect the changing patterns of sport participation and increased demands of sport and sport specialisation on our younger athletes. The classic presentation of an ACL injury is that of a noncontact twisting or pivot shift injury to the knee. The patient often reports feeling a pop in the knee and a moderate to large effusion or knee swelling typically ensues. A number of studies have shown a higher incidence amongst female athletes then compared to male athletes, up to 3 times higher.

This may reflect anatomic and biomechanical differences. There have also been studies showing oestrogen receptors on the ACL and levels of the hormone relaxin also present in the ACL which may have some influence. Conclusive evidence for this trend however is lacking.

Risk factors for an ACL injury maybe classified into non-modifiable and modifiable. Non-modifiable or intrinsic risk factors include certain anatomic variations including increased Q angle, increase posterior tibial slope, narrow intercondylar notch width and generalised ligamentous laxity. Modifiable risk factors include the biomechanical and neuromuscular factors and it is these risk factors that we can influence through proprioceptive and neuromuscular rehabilitation programs and therefore decrease the risk of ACL injury. Some of these modifiable risk factors that are associated with high risk of injury include decreased hip and knee flexion angles upon landing, increased internal hip rotation and dynamic knee valgus and a higher quadriceps strength relative to hamstring strength.

ACL prevention programs

ACL prevention programs aim to correct modifiable risk factors through neuromuscular and proprioceptive training. This is not a new concept. Caraffa back in 1996 studied 600 semiprofessional Italian soccer players. Half the athletes under went proprioceptive training and half did not. He showed almost 7 times the incidence of ACL injury in the control group compare to those that underwent proprioceptive training. Many studies have since replicated this trend. Mandelbaum in 2005 developed the prevent injury and enhance performance program (PEP). This program involves a comprehensive neuromuscular program of warmup activities strengthening exercises stretching techniques plyometric exercises and finally soccer specific agility drills. They showed A 70% decrease in ACL injury rate in the PEP trained players. Subsequent studies have shown a cost effectiveness in these neuromuscular preventative programs and it is recommended that they be universally applied. Many organised sports have now implemented such programs including netball Australia with their Knee Program and FIFA has implemented the FIFA 11+ and FIFA 11-Kids workbook for injury prevention.

Treatment of ACL injuries in children

The goals of treatment in the paediatric patient with ACL injury are:

- restore stable functioning knee to allow an active lifestyle

- reduce the risk of further injury and long-term consequences such as degenerative joint disease

- minimise the risk of growth disturbances.

The age of the injured athlete and the remaining growth left influences the discussion around the treatment options with the parents and the athlete. In addition to the chronological age it is important to assess bone age and stage of development. In my practice I obtain a bone age by xraying the patients left hand and comparing that to the bone ages of the Greulich and Pyle Atlas and assess development with the Tanner stages. Knowing these allows a discussion around potential treatment risk to the physes and remaining growth about the knee.

The treatment options are essentially:

- High quality rehabilitation to facilitate dynamic lower limb control and biomechanically sound movement. Activity modification is important with this to provide the best level of protection against repeat injury and damage to the meniscus. Provided functional stability can be achieved this is a good option in the very young skeletally immature patient with the view to delayed ACL reconstruction when they have matured along the Tanner stages.

- Prehabilitation with ACL reconstruction and post-operative rehabilitation. Whilst the literature is not clear, I think that reconstruction provide the athlete with a higher level of return to sport and is likely to be meniscal protective. The type of reconstruction depends on the age and stage of development. For the very young a physeal sparing technique is recommended (Tanner stage 1-2) such as an all epiphyseal or an over the top technique. A transphyseal reconstruction with soft tissue graft and extra physeal fixation has been shown to have very low rates of physeal injury (Tanner stage 2-4). For the adolescent with closed physes an adult type reconstruction with aperture fixation can be undertaken.

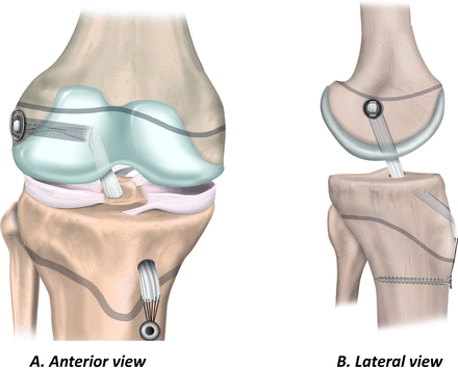

Physeal sparing (all epiphyseal)

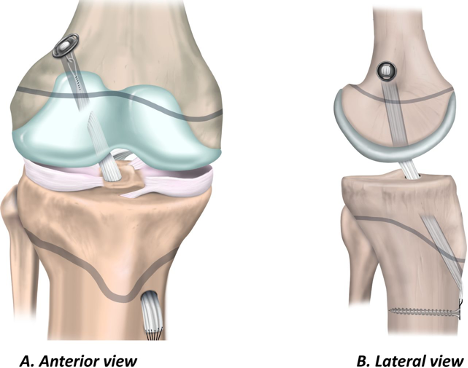

Transphyseal with extraphyseal fixation